At whose expense are service learning and diversity courses effective? Can U.S. education policy stop telling poor students what to do (and instead provide them with resources and opportunities)? How can we avoid reproducing oppressions in our social justice work in education?

These are just some of the difficult and important questions addressed at this year’s AAC&U Annual Meeting, “Building Trust in the Promise of Liberal Education.” Without a doubt, the most common refrain, resounding over and over again, was “so what do we do now?” Now that Trump is president and the intersecting axes of discrimination and oppression are multiplying, intensifying, and sanctioned by the U.S. president.

To back up a bit: the AAC&U is the Association of American Colleges & Universities. Two thousand college and university administrators, presidents, deans, faculty, graduate students, and (to my delight) undergraduates, from all over the world, attended this year’s conference in San Francisco. I was there receiving the 2017 K. Patricia Cross Future Leaders Award and to find out what this AAC&U organization is all about. Without a doubt, the highlight of the conference was getting to know the other recipients – graduate students from different schools and disciplines who are transforming education in order to improve society. Their resumes are impressive, to say the very least, but in person they far exceed what a professional bio can capture. Their generosity, kindness, fierce intellect, humor, determination, care, and bravery are, as Lee Knefelkamp, quoting Maxine Greene, kept saying “a light in dark times.” I hope we will remain friends for years to come.

Glancing at the program, there were a lot of things that made me itch: from the very term “liberal education” (in intersectional feminist and antiracist work, liberalism is often the enemy) to the predominance of buzzwords I typically associate with conservative, neoliberal rhetoric: innovation, excellence, and entrepreneur, among them. But as I learned throughout the conference, these terms can be used strategically to advance feminist and antiracist projects with real, material, and redistributive effects. Moreover, I learned that it is inadequate and inaccurate to simply blame the administration for all the inequities of higher education. From K. Patricia Cross’s 1969 talk “Some Correlates of Student Protest” to AAC&U President Lynn Pasquerella’s 2017 address to women faculty and administrators, I have realized that many administrators want to support activist students and faculty and actually meet their demands. My favorite line from Cross’s 1969 speech, a response to the student protests occurring at college campuses nationwide, delivered at the NASPA-Center for Research & Higher Education Conference (theme = “The Student Dean—A Campus Activist?”): “If we ever wanted student involvement in the learning process, we have it now.” My interpretation? For those of you, today, who believe in student empowerment, engagement, and civic responsibility: you better be listening to, advocating for, supporting, and working with the activist students on your campuses who are demanding

- greater transparency in policy decisions

- that campuses acknowledge their histories of racism

- more resources for campus diversity programming

- increased faculty diversity

- diversity training for faculty

- more inclusive curricula

- better mental health services

Why these demands are not met more often, if students, administrators, and faculty are willing to work together, is a subject I will continue to explore.

Below are some highlights from the plenaries, workshops, and panels I attended, all of which helped me see the relationship between education and social justice in more nuanced terms.

I was very grateful for an interactive opening forum Wednesday night after a long flight from JFK – a welcome reminder that active learning is especially important in those 7:45 am courses I kept getting assigned to teach, and late in the evening, when those of us still on East Coast time were exchanging commiserative glances across the table. In “Predict the Future By Inventing It: Accelerating the Pace of Change in Academia,” Humera Fasihuddin, Leticia Britos Cavagnaro and their (largely undergraduate) team of University Innovation Fellows led us in the kind of design-thinking activities they promote on campuses. University Innovation Fellows bring groups of students together to identify problems on their campuses and work together to address these. One example that stands out in my mind is an undergraduate student at Dalhousie who wanted to figure out how university resources could go towards the Syrian refugees residing in Halifax and navigated the hurdles of institutional bureaucracy to organize a weeklong coding camp that taught the refugees programming languages. In our forum, we practiced the kind of “design thinking” they advocate by working together to redesign the conference introduction experience.

The recent women’s marches were a shared referent throughout the conference, especially at the women’s networking breakfast. President Pasquerella delivered an important speech on “Glass Cliffs, Queen Bees, and the Snow Woman Effect: Persistent Barriers to Women’s Leadership in the Academy,” which cited many of the studies included in Gender Bias in Academe, a bibliography I maintain with Cathy N. Davidson. I was especially impressed by how Pasquerella wove the findings from these data-driven studies about structural gender and racial bias into a compelling narrative that concluded with a call to action: “so what are we going to do now? What are we going to do about all this?” This was not, as I first assumed, a rhetorical question. Audience members jumped to their feet to contribute examples of how they are addressing systemic injustices on their campuses. I should add that Pasquerella was introduced by Caryn McTighe Musil, who invoked the recent film Hidden Figures to remind us that ours is not the first moment in which women, and especially women of color, have been called upon to save “a drifting white man in a suit who can’t steer,” and have been un- or under-valued for this labor. While we joined together to celebrate women leaders, McTighe Musil reminded us that very often some of our most courageous leaders do so behind the scenes and with titles that don’t explicitly designate their leadership. Speaking of which, one attendee encouraged leaders to review the resumes of every woman and person of color who reports to them, and make sure their titles and job descriptions accurately reflect their vast and varied leadership responsibilities.

The women’s breakfast was followed by a galvanizing discussion among President Pasquerella, Beverly Daniel Tatum, Sara Goldrick-Rab, Michael Roth, and Jeff Selingo on improving liberal education in a climate of anti-intellectualism and decreasing public tax dollars. As Colleen Flaherty reported in her summary of the discussion, this involved “being more open about areas in which higher education has been weak.” There seemed to be consensus that major failures include our inability to assert the relevance and legitimacy of liberal arts education (from classrooms to board meetings) and our collusion with what Sara Goldrick-Rab identified as the “high-tuition, high-aid” model, which, in fact, has never worked.

Beverly Daniel-Tatum, former president of Spelman College and author of “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?” and Other Conversations about Race, received the prestigious Ernest L. Boyer award for her lifetime work in education. In this year, the 20th anniversary of Daniel-Tatum’s publication, she helped us see all of the ways in which things have not gotten better, and are, in many regards, more unequal and segregated than when the book was first published in 1997.

At the Future Leaders Panel, Lee Knefelkamp honored her promise to K. Patricia Cross to ask us the difficult questions about how we are changing higher education to better serve our communities. I was happy to share with the audience my dissertation research, the ways that teaching at Queens College has shaped my decision to pursue higher education by allowing me to combine my passions for creativity and social justice, and to implore the audience to think beyond the scholarly peer-reviewed journal article as the measure of scholarly excellence. I will say it again here: if we want to support liberal education and the missions of our universities, we need to change what counts as knowledge production so that videos, blogs, digital scholarship, teaching workshops, art exhibits, public events, community organizing, activism, performances, collaborative work, and mentoring are encouraged, valued, and rewarded.

Other highlights included a breakfast conversation on the purpose of education led by Richard Prystowsky from Lansing Community College. I have always thought about the question of student engagement and success at the level of my own classrooms, and it was a pleasure to think about this question from a different administrative perspective – thinking about how to design curricula and train faculty for student success. The panel on intersectionality, led by Lee Knefelkamp, Janie Ward, and Leeva Chung, gave us helpful frameworks for thinking about our students in terms of the overlapping and interdependent systems of disadvantages and discriminations in which their lives are unfolding. One standout moment was Dr. Ward’s assessment of how the diversity training efforts at her women’s college failed because they recentered whiteness and didn’t help students of color. An audience member added to this conversation by sharing a remark from one of her black students: “I don’t want to be in the room while someone realizes I’m human.” I’m not shocked but angered at how “diversity” has yet again been shown to re-entrench racial inequality. We can do better than this.

There was an emphasis throughout the conference on redesigning education, and I was glad to see that people seem interested in the genealogies of feminist and antiracist educational work that I explore in my dissertation.

Throughout the panel, Twitter served as a lively conversation space where many attendees shared our enthusiasm for certain ideas and voiced concerns about what perspectives were missing. At one or two panels, I found myself missing the perspectives of our colleagues at community colleges, where resources are often scarce but creative approaches to teaching and learning flourish. But overall, I found that AAC&U members work hard to practice what they preach in terms of inclusivity, active learning, total participation, and interactive dialogue.

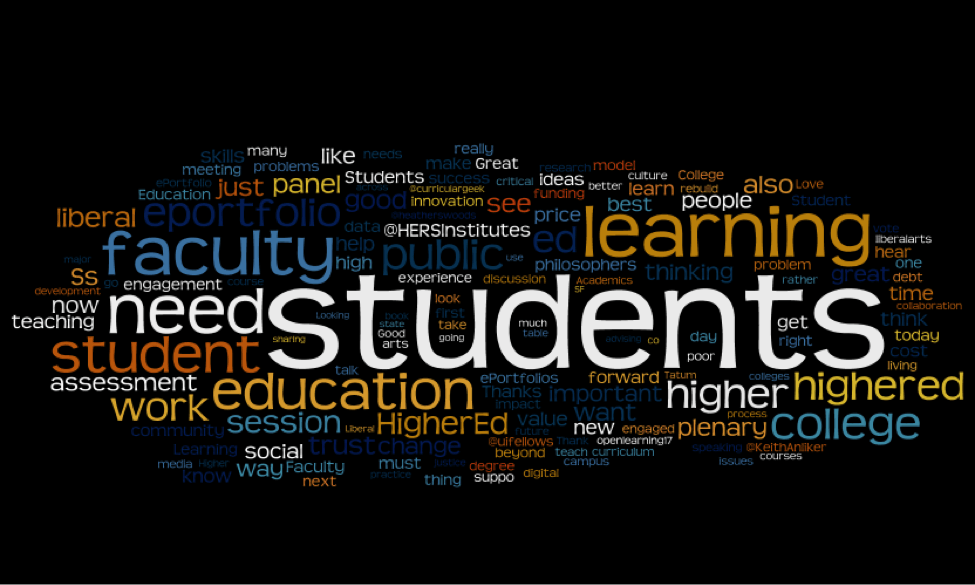

After all was said and done, I made word clouds to compare the conference as it was described in the program and as people documented and discussed the proceedings on Twitter. These word clouds illustrate how the conference program emphasized universities, but among Twitter users the clear focus was students. You can view all tweets from the conference using #AACU17.

A good feminist always considers those who did the labor and provided the resources to make our lives possible. Thank you K. Patricia Cross for offering me this invaluable opportunity to learn from the very people that many of us who are interested in change are often quick to vilify. A huge thank you to Suzanne Hyers for her meticulous planning, generosity, and making us all feel welcome. Thank you to Lee Knefelkamp for being our fearless leader and for making the entire experience FUN. Thank you to Kandice Chuh and Cathy N. Davidson for nominating me and sending letters of support.